|

Squatters

The Most Responsive Unreached Bloc

BY

Viv Grigg

What if the Muslim or Hindu worlds doubled every ten years? What if they were some of the most responsive peoples on the globe? How would this affect mission strategies?

Urban squatter areas are a bloc as large as these two worlds, doubling every decade. All indicators show them as responsive peoples. Logically, missions must adjust their strategies to make them their priority target.

The majority of migrants to the mega-cities will move into the slums (Bangkok), squatter areas (Manila), shanty towns (South Africa), bustees (India), bidonvilles (Morocco), favelas (Brazil), casbahs (Algeria), ranchitos (Venezuela),

ciudades

perdidas (Mexico), barriadas or pueblos jovenes (Peru). I will use the term squatter areas to refer to all these settlements.

These tend to be slums of hope whose occupants have come in search of

employment, found some vacant land, and gradually become established, building their homes, finding work, and developing some communal relationships similar to the

barrios or villages from which they have come. In the slums of hope, social forces and expectations create a high degree of receptivity to the gospel.

Other Urban Poor

Squatter areas need to be differentiated from the inner city

slums-decaying tenements and houses that were once good

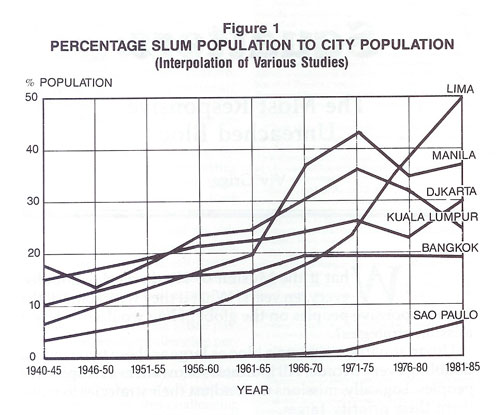

Figure 1 PERCENTAGE SLUM POPULATION TO CITY POPULATION

(Interpolation of Various Studies)

middle and upper, class residences. These may be described as slums of despair;

they are home to those who have lost the will to try, and those who cannot cope.

Yet here too are re- cent immigrants living near employment opportunities, and students in the hundreds of thousands, seeking the upward mobility of education. In these slums of despair there is little social cohesion, or positive hope that facilitates a responsiveness to the gospel. As they are older poor areas of several generations of sin, they are not responsive areas and hence not as high a mission priority. It is more strategic to focus on the squatter areas.

The Extent of the Squatter Areas

Estimates of the rates of growth of the squatter areas indicate that they are

growing faster than the cities at annual rates of about 6-12 percent. The

squatter areas of Kuala Lumpur, for example, grew at an average annual rate of 9.7 percent from 1974 to 1980. Much of this can be attributed to the growth rate of cities in general. Worldwide urban growth has been pegged at 2.76 percent a year. Thirty to sixty percent of this is due to migration from the rural areas. At that rate, city populations will double in twenty years. But the mission field among the squatters will double every ten years or so.

In the year 2000,2,116 million or 33.6 percent of the world will be in cities in less developed regions and 40 percent (a conservative figure) will be squatters (846 million). This would indicate a world that is about 13.6 percent squatters by the year 2000-a bloc nearly the size of Muslim

or Hindu populations, doubling each decade-a distinct entity in their own right

for evangelization. When one includes both slum and squatter figures for these

Third World mega-cities, in none of them is the percentage of poor less than 19

percent. In many it is over 60 percent. Including the less reachable, decaying inner city slums, and street people in these cities, a reasonable estimate is that 50 percent of the population of these cities in the year

2000

will be urban poor (1 billion),

which is 16.8 percent of the world's population.

The urban poor as an entity can- not, in contrast to the squatter communities, be generalized as a reach- able bloc with cultural affinities. They do not identify themselves as communities with common characteristics or affinity for other types of urban poor. The urban poor as a larger class are defined in contrast to the people of the city, rather than as an entity in themselves.

Most Responsive International Cultural Bloc

Not only do the squatters share a common economic history and sys- tem that is

nearly universal, but they also share universal religious characteristics, an animism that is far stronger than the prevailing "high" religions. Cultural characteristics in the slums are as much universal as they are sub-culturally related to the

preva1ent cultures. We may define them as a cultural bloc with as much ease as we define Muslims or Hindus

who span a broad range of ethnicity and culture. Animists in general are more reachable than other high religions.

Socially, each squatter community of reasonable size perceives itself as a

distinct social entity, linked to the city, but with a life and society and

subculture of its own. In any city, the squatters have coping strategies

independent of middle class life, including middle class religious life to which

they have little or no relationship. If you have ever been present when two

squatter churches meet, you would under- stand the affinity evident between these people as a social class with similar occupations and patterns of residence.

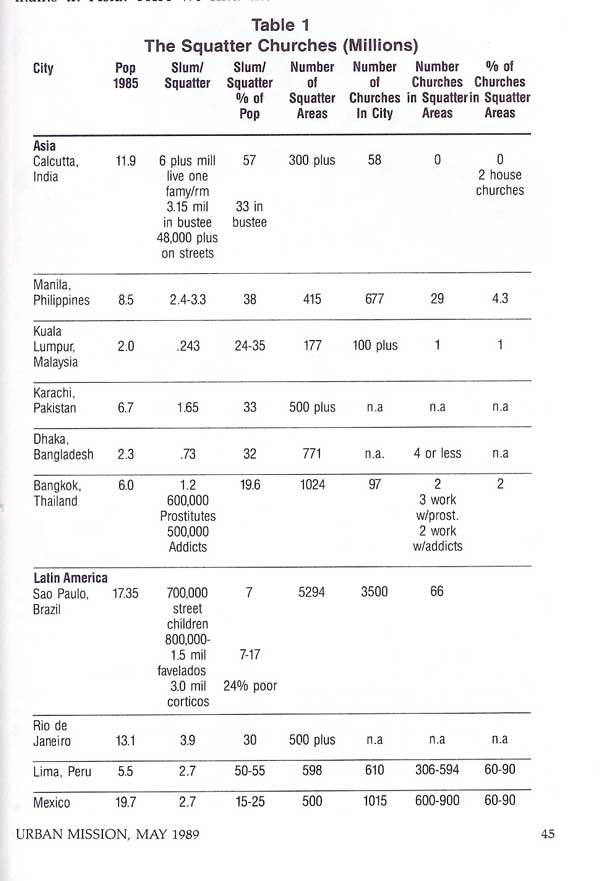

Figure 2

CHURCHES IN CITY

AND SLUMS

Language in the squatter areas tends to draw migrants together as all learn to speak the lingua franca

of the city. Yet almost all realize that they cannot read and write properly and

are, unlike the middle class, uneducated. As a result, ethnic barriers lower but a strong class barrier towards the middle class emerges.

Such communities are more responsive than the closed rural village or the isolated middle class person.

Poverty creates a positive responsiveness to the gospel, according to the apostle James. The changes migrants go through create a responsiveness.

Faced with universal responsive- ness in the international subculture of poverty in these squatter areas, we must develop specific missions and plans for evangelization.

Where are the Squatter Churches?

Where are existing movements among the poor? Figure 2 and Table 1 summarize recent research into church growth in the squatter areas and slums in various cities.

Asian Cities: Mission

Target

The Target of world evangelism, the greatest unreached areas, remains in

Asia. Here we find the

slums of the cities relatively unreached by the love of God. Nowhere in Asia, with the exception of Korea, does the church in the slums have

more than four percent of all the existing churches in the city. In each city,

there are only a handful of slum churches. In no city is there a movement of poor people's churches.

The urban church of Asia is a middle class church. "Urban mission" as a call unfortunately increases this bias. The target needs to be redefined urgently as "urban

poor mission:'

Bangkok

The church in Thailand has faced much resistance to growth, but in the last ten years a growing openness has developed. The Church Growth Committee estimates that there are ninety-seven churches in Bangkok, about 25 percent of which are relatively small and new (i.e., one church/6O,000 population).

However, in the 19.6 percent of the city that constitutes the 1,020 slums, there are only two churches and two house groups (1986). That is, only two percent of the churches are among the migrant poor, many in shacks of galvanized iron, others in

overcrowded but well-built old-style Thai houses. Many of these migrants are

from the more responsive North and Northeastern Thai ethnic groups. In 1986, we

were able to initiate the first team of foreigners to live in these slums. For

the 600,000 prostitutes, there are only two ministries and for the 500,000 drug

addicts, only one drug center.

Manila

Manila is more evangelized than any other Asian city, because of the influence of a Catholic heritage. There are 677 churches. But at last count, there were only twenty-nine church-planting ventures among the 500 squatter areas that contain over 30 percent of the 8.5 million population. There is still the need for some- one to develop a church-planting pattern that will generate an urban poor movement such as has occurred in Latin America.

Kuala Lumpur

Kuala Lumpur, in Malaysia, is a

dynamic city, growing rapidly and exploiting well the natural resources of its

country by utilizing money pouring in from its Muslim brothers. The 24 percent

of its 2 million squatters include 52.5 percent reachable Chinese and 14.9 percent reachable Indians. It is one city where there has been a .consistent and reasonably humane program for uplifting these poor. A former rock musician turned accountant-evangelist heard the cries of the poor and is building a church among them.

Chinese and Indian communities are open to the gospel. In general, the Chinese Malaysian church has been locked into an older style of church growth-oriented evangelicalism which does not understand issues of poverty, or a newer Pentecostalism that is dominated by a theology of affluence. Yet in the last ten years the church has become more open to ministry among the poor as a result of the charismatic renewal.

Dhaka

The destitution of the poor in Dhaka is greater than in any city, even Calcutta,

perhaps because Bangladesh is one of the most bereft nations on earth, despite

its luxuriant agricultural resources. Houses are made of mud thatch, a few feet

tall, and the people possess virtually nothing. This year the poor number 3

million. By the year 2000 that figure is projected to be 20 million. The majority of these poor will become squatters.

There are Hindu converts in the 771 bus tees. But the majority of people are Muslim and have never heard or seen Jesus. The country is open to many forms of foreign development assistance and this gives open doors

to respond to the cries of the poor.

Calcutta

Sixty-six percent of its 10 million people live one family per room. Two and one half million live in

bustees, 500,000 in refugee areas, 48,000 (officially)-200,000 (generally accepted figure) live on the streets. There are other migrant squatter communities with homes of thatch and mud. There is no church, only two small house groups among these slums. Of the fifty-eight churches in this city of 10 million, many contain the poor, for 60 percent of the city are underemployed. None is a church of the slums reaching out to the slums.

Jesus has sometimes been seen in these slums in the persons of a few varied

saints, for there are many good Christian aid programs. But he has not been

heard for two generations and his body has not been formed: there are none to live among the poor and form it.

Latin American Cities:

Mission Source

In contrast with Asia, Latin America's cities are centers of amazing kingdom

growth. The majority of the churches in Latin cities are among the poor. Why

this difference? And what are the implications for missions?

Lima, Peru

Once the capital of Spanish South America, today Lima is predominantly a city of 5.5 million migrant, Hispanicized Indian peoples. In 1940, 35 percent of Peru was urban. By 1984, 65 percent lived in urban areas. Thirty percent of the total population live in Lima.

These waves of landless, homeless people have resulted in the sprouting of

pueblos jovenes (young towns), which now comprise 50 percent of the city. Most spring up unplanned and without government assistance. After a period of time, facilities are extended to them by the government including water, roads, and electricity. There are 598

pueblos jovenes, mostly on desert or mountains surrounding

the city. There are also hundreds of thousands in overcrowded inner city tenements known as

tugurios.

Of the 610 churches and 1.93 percent evangelicals in the city, church leaders indicate that 90 percent of the churches are in the

pueblos jovenes. There is, in Lima, a movement among the urban poor of a size much larger than in any Asian city. However, 598

pueblos jovenes compared to 610 churches means that there are still many without churches.

The tugurios, the inner city tenements, are probably largely unreached as no church leader I talked with was aware of believers or churches in these areas.

Mexico

The rich and poor among the 18 million people of Mexico City often live side by side on the same block. Other poor live in the

cuidades

perdidas (lost cities), where rundown and abandoned buildings become home. The School of Civil Engineers in 1984 counted 500 of these

cuidades perdidas with 2.7 million people. There are also areas of squatters known as

paracaidistas (parachutists)

where 200 families suddenly descend overnight onto unused land, moving from the

cuidades perdidas. The 1985 earthquake left 40,000 families relocated into what has become for them permanent-temporary housing.

Again, of Mexico City's 1,015 churches, the majority are among the poor.

Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Sao Paulo is a vibrant, sprawling metropolis that covers an area of 1,400 square miles, where 15 million people live and 106 languages are spoken. It has 115,000 industries, three major soccer teams, and thirty- four universities. Poverty is far less than in other world class cities: only 800,000 (1982) lived in the

favelas-a mere 7 percent. But this figure hides the reality of an estimated 500,000

Brazilians who are moving annually to Sao Paulo and the 3,000,000 (17 percent) living in

corticos decaying, inner city buildings. Only 5 per- cent of favelados

in Sao Paulo have claim to their land. A mere 3 percent of them earn minimum salaries.

Seven hours away, the city of Rio explodes into the skyscrapers dotting the beaches. In the midst of the wealth and the tourism lie some of the most beautiful

favelas in the world. If one is going to be poor, it is smart to be poor in the most beautiful city in the world-and about 30 percent of the population are.

There are more churches in Sao Paulo and Rio than in other cities of Latin America or Asia

5294

in Sao Paulo. There is a greater movement among the poor. Many

favelas have three or four churches. The majority of these are Pentecostal, particularly Assembly of God.

Poor Peoples' Churches

Traditional churches are virtually nonexistent in any country among the urban poor. My research con- firms this. Traditional churches that target the urban poor should plan for Pentecostal-style leadership,

worship, and theology if they would succeed.

These churches have what poor people need. Simple patterns of noisy, emotionally healing worship, strong authoritarian leadership, and many legalistic rules. They are very dependent on the leading of the Spirit of God. They tend to lack in good Bible teaching, and reject book learning, partly because of the rapid growth which precludes extensive training of pastors and deacons. (This last factor is neither an essential

nor healthy characteristic. Wesley modeled a way of developing theologically competent leadership

among the poor). I have not found in any city a church formed among the poor

that was not the

result of healings, deliverance, and signs and wonders.

Movements in Latin America; Nothing in Asia

There has been a dynamic of church-planting in Latin rural areas. Then, as migration has occurred, the pastors have moved with their people to the cities and the

favelas and pueblos jovenes. Why has the same pattern in Asia not resulted in churches among the urban poor?

Perhaps the reason, assuming that mission over the last decades has predominantly been North American,

is that the middle classes in Latin America have been identified with the

Spanish and Portuguese, who have traditionally been closed to the gospel and

opposed to North American influence. The poor, on the other hand, come from the

more oppressed indigenous cultures with a suppressed opposition to the Spanish culture (though they are attracted by it). This is in contrast to the Asian scene, where a positive attitude to- wards American culture by the up- per and middle classes has meant a responsiveness to mission efforts.

Next Phase: Latin Poor Missions to Asia

It is possible that God will raise up some apostles from among the middle class church of Asia to bridge the gulf to their own squatter communities. Perhaps he will call some rich to live among the poor.

On the other hand, why not steal some of these trained Latin Americans-perhaps several hundred- to catalyze this? They have the faith. In fifteen months, Pastor Waldimar of Brazil, while developing the project

SERVOS Entre os Pobres under his mission KAIROS, has recruited 170 potential missionaries for this task. Bankrupt Brazil does not

have the finances for their transportation or support. By faith they wait on God

who will overcome this barrier. We would not expect significant church-planting

among the Asian squatter areas from the affluent West; affluence makes it too

hard to live among the poor. Mission to the poor tends to be defined as development. Traditional Western theology and structures do not meet the needs of the poor. I say this despite having set up two missions from Western nations to accomplish this goal and having an extensive background in community development.

Foreigners, WASP or Latino, are an important catalyst to the national Asian

churches, but only a catalyst. We must model in such a way that indigenous

works, indigenous leadership, and indigenous missions

emerge. The aim is not missions. This is too small. Nor is it church growth. This is too limited. The aim is the discipling of the peoples- indigenous squatter discipling movements. These will not emerge from highly financed mission pro- grams. Missions that would catalyze these must be missions of workers who choose lifestyles of voluntary poverty among the poor.

God is calling for Latin missions with commitments to lifestyles of

non-destitute and incarnational poverty (and for many, years of voluntary

singleness) to catalyze indigenous movements of churches among the unreached squatters of Asia.

How Much Could God Do?

God will do what we ask. As you

read, would you bow and pray for:

1. Two incarnational workers in

every squatter area.

2. A church in every squatter

area.

3. A movement in each city

among the poor.

4. Transformation of slums and

squatter areas in some cities.

5. Incarnational workers from among the poor who can affect economic and social structures and political options.

6. Mission leaders to make the

squatters a priority.

7. A major thrust from Latin

America to the Asian squatter areas.

Abraham prayed for a city. God heard.

Nehemiah prayed for a city.

God gave.

Jonah spoke to a city.

God moved.

What are we trusting God for?

NOTES:

Grigg Viv,

URBAN MISSION, Vol.6/ no.5 May, 1989,

pp 41-50.

| |

|

![[Company Logo Image]](../images/Bias-t1smallerfile.jpg)